Recently, I asked a few friends about what they thought of “Australian culture”. One mentioned the beaches and the accent. Others referred to the iconic wildlife, such as kangaroos, koalas, and poisonous snakes. Most think that we are “laid back”. The opening line in Britannica’s entry on Australian culture says that “Australia’s isolation as an island continent has done much to shape—and inhibit—its culture”. It appears that Australian culture is almost a quasi-culture, with our most notable contribution to cinema being Crocodile Dundee and Mad Max, perhaps. Though we do have a stellar track record of supplying Hollywood with talent such as Margot Robbie, Nicole Kidman, Cate Blanchett.

This raises the question: what exactly is Australian culture?

“We've got more culture than a penicillin factory”

- Barry Humphries

In this essay I attempt to explore Australian culture through several lenses — the art of Vincent Namatjira, the stand-up comedy of Will Anderson, a book on Australia’s economic history, and a play at the Sydney Opera House.

art and egalitarianism

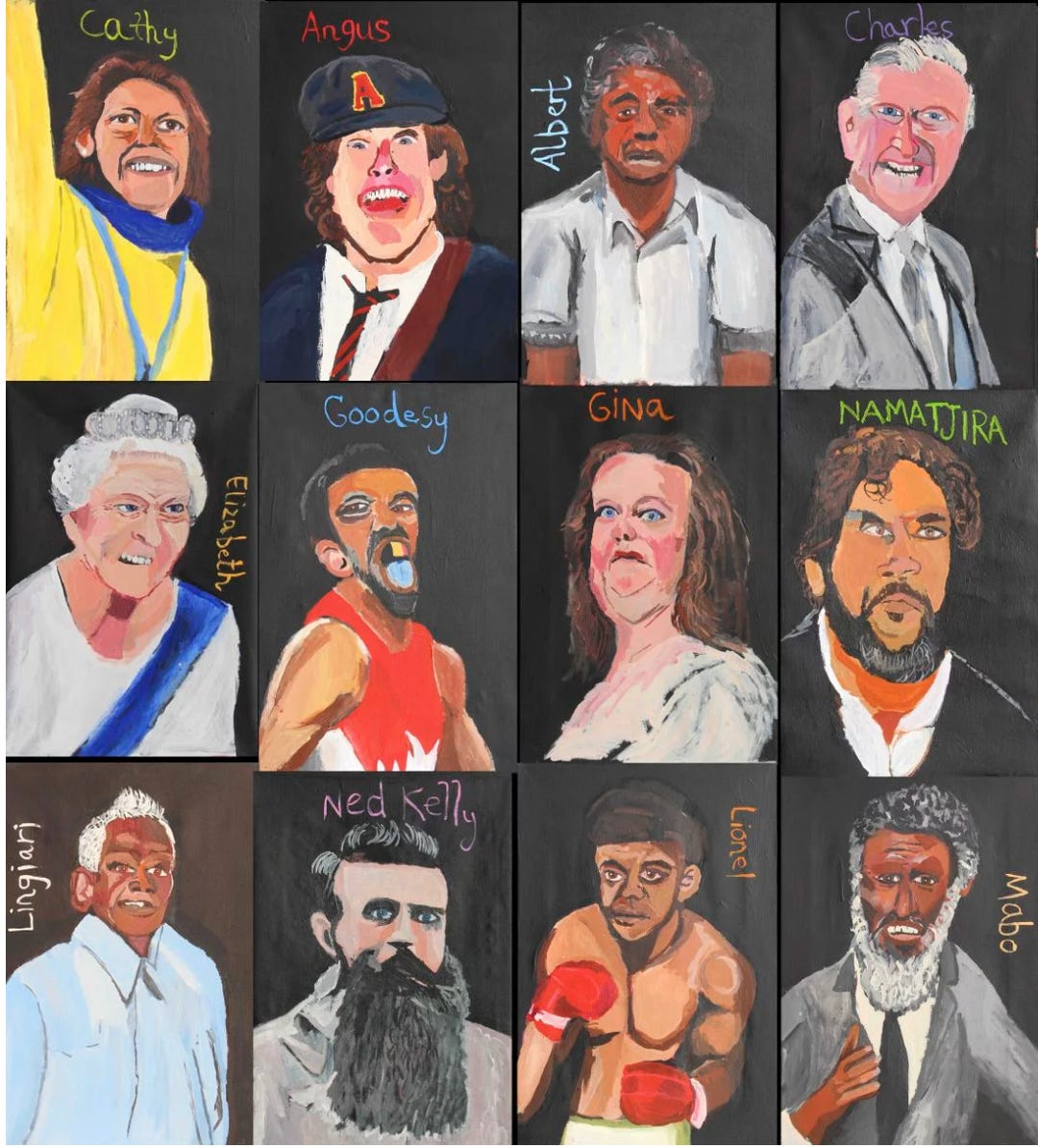

A few weeks ago, my mum sent me a news article about Gina Rinehart, asking the National Gallery of Australia to take down her portrait. Gina is Australia’s wealthiest woman, who made her fortunes managing her late father’s mining and resources company. The portrait, painted by Vincent Namatjira, an Archibald-prize winning portraitist, is shown below. “She looks crazy” my mum said. The Archibald prize is the most prestigious art prize in Australia.

I wondered why Vincent’s art, which mostly consists of fugly portraits of various political and social personalities, was so renowned. What earned him the Archibald prize? Was it his artistic technique, or the ideas behind his work?

On artistic technique alone, I have no doubt that Vincent is a technically talented artist. Although his portraits are fugly, one could instantly identify the subject. This suggests that he has a keen sense of proportion, and excellent observational skills. He captures the essense of his subjects, before deliberately rendering them in an exaggeratedly fugly, awkward and janky manner.

Apart from this, I find nothing particularly striking about his art. His colours are basic, just flat swathes of paint layered over each other, and the composition is mundane. So, why did he win the prize?

Many suggest that Vincent’s art is worthy of recognition because it “satirises” powerful people, but I believe there’s more to it than that. Vincent doesn’t limit his fugly portraits to billionaires, politicians and royals like Gina Rinheart, Donald Trump or King Charles. He also depicts famous individuals with Aboriginal and Indigenous heritage, like Kathy Freeman and Adam Goodes (see Goodesy below 😂). Moreover he pokes fun of Ned Kelly, the most romanticised outlaw in Australian history. Vincent’s self-portrait is equally unflattering, as are the portraits of his friends. I noticed key similarities between Ned Kelly and Vincent: both are larrikins and troublemakers who were victims of the system during their youth, and both embody Australian characteristics.

As seen in the image above, Vincent makes Ned Kelly look like a tumblr goth 🧛🏻♂️. Born in 1854 to two Irish convict parents, Ned was an infamous outlaw. A year before his death at the age of 25 during a police shootout, he wrote a manifesto. In it, he railed against the wealthy British settlers (many of whom owned large swathes of land in the penal colony) and the corrupt British officers, justified his murder of three policemen, and urged readers to give to the poor. In one very poetic paragraph, Ned wrote:

… my brothers and sisters and my mother not to be pitied also who has no alternative only to put up with the brutal and cowardly conduct off a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or english landlords…

Ned’s writing style mirrors Vincent's painting style—both are very anti-privilege and disdainful towards the wealthy and famous. This, I believe, is the reason behind Vincent’s artistic fame. Not because of his artistic technique, Indigenous heritage or the fact that his works satirise the rich and powerful. His art is renowned and award-winning because it represents the idea of bringing everyone down a peg or two, so that everyone is on equal footing. Vincent is thought to have said, “I see myself as a royal.”

Vincent's art encapsulates the ethos of Australia. Every aspect—his subject matter, technique, personality, life story, and style—is a reflection of what Australia stands for. He is the very embodiment of Australian values, history, and national character.

The Guardian’s claim that “he takes aim at the rich, white, and privileged” is misguided. In reality, Vincent takes aim at everyone, including himself.

comedy and national identity

A few weekends ago, I attended a standup comedy show by Will Anderson. Will started his career as a journalist before pivoting to comedy. He is rather well known in Australia, though a bit of a nobody in an international context. My housemate wanted to see him — I am no fan of standup comedy. She saw him open for Ronnie Cheng, who is way more famous globally, and has his own Netflix special. She found herself enjoying the opening act by Will more than the main show by Ronnie.

What stood out to me, though, was how “Australian” his material was, and how unsuitable it would be for an American or global Netflix audience. He talked about growing up on a dairy farm, milking the cows, wearing a “skivvy” (a type of turtleneck shirt) at the beach, and Ned Kelly(!). Will joked about how Ned Kelly has been immortalised as a mythical figure, forever wearing his iconic bullet-proof mask. He also talked about how common it was, growing up in regional Australia, for your next door neighbour to live 40km (around 25 miles) away.

He continued delivering other Aussie jokes, including a bit about Harold Holt, our former Prime Minister who famously disappeared while swimming in the ocean, his body never to be found. Will joked that ever since that embarrassing incident, Australians felt they had to overcompensate by winning a record number of olympic medals for swimming. I thought that this joke touched on a very Australian thing — the beach as a treacherous place (Will’s younger brother almost drowned at the beach). It is common for lifeguards and helicopters to sometimes surveil popular beach areas for drowning people, or sharks, or sometimes both.

After the show, me and my housemate tried to recount our favourite jokes. But we had trouble pinpointing specific jokes he told. This was because his jokes were not standalone — they were connected by a cohesive narrative, and told of his story as a young boy, a young man, and now as a gen x-er. It was like a long, funny story about his life, and about Australian culture: Self-deprecating, a strong connection to places like the farm and the beach, and the pervasive feeling of being tyrannised by long distances. We are, after all, an island continent that is geographically very isolated from the rest of the world.

Australia’s economic history

Australia’s economic past has shaped much of its current attitudes towards work, fairness and social welfare. So to understand Australia’s culture, it is essential to appreciate its economic history.

Much of what I know about Australia’s economic history comes from Edward Shann’s book, an Economic History of Australia. Economic history, you say. Yawn. But Ed’s work is not your typical econ 101 textbook, it is a piece of literature. Ed suffered from nervousness all his life, and died prematurely in 1935 after falling out of the window while trying to get air during one of his nervous bouts. His book was published posthumously in 1948.

I won’t go into his entire book, but just pick out bits which I think are interesting and revealing.

Edward dedicates the first chapters of his book to the early decades of the young Australian colony, from 1778 (when the First Fleet landed) to 1820ish. In one of the paragraphs, he writes:

Each of the benevolent despots, from Phillip to Macquarie, groaned under the load of responsibilities which the prison communism heaped upon his shoulders, but none with more reason than the first.* His command was a mere dump for human rubbish.

In the paragraph above, Ed describes how Australia’s first governors (“benevolent despots”) had to manage the “prison communism”, referring to the early penal colony they were tasked with overseeing. He calls the British officials who accompanied the benevolent despots “a mere dump for human rubbish” (they were reluctant to discipline the convicts). He also said that the men were so miserable that he was advised to capture Pacific Islander women to help keep the men company.

Such was the misery of existence there that, out of sheer pity for the proposed victims, Phillip refused to correct the disproportion of the sexes by sending ships to take women from the Pacific Islands, as bidden by his instructions.

Ed goes on to write about the paternalistic nature of the first few decades of Australia, a necessity born out of the colony’s circumstances. The colony struggled to grow their own food and become self-sufficient. The colony relied on rations provided by the British government, and everyone — convict and governor alike — had to share these rations. Governor Philip also allocated land to emancipated convicts. The National Museum of Australia says that these actions “ensured the colony’s survival and initiated an egalitarian spirit still prized in Australia today”.

However, the notion of an egalitarian spirit in early Australian society is somewhat complicated. In reality, the social structure was highly stratified. British officials and wealthy free settlers occupied the top of the hierarchy, while convicts, bushrangers (outlaws), and swagmen (nomadic menial workers) found themselves at the bottom. Some argue that this has resulted in a phenomenon called “tall poppy syndrome”, which has been widely and discussed and analysed on Reddit.

Ed goes on to suggest that the paternalistic nature of Australia persisted throughout the 1800s and into the 1900s. This was because the colony continued to rely on British supplies and, more importantly, capital to fund its infrastructure, as it gradually transitioned away from using rum as a currency. Interestingly, rum played an important role in helping pry the young colony out of its communistic arrangements, by providing a medium for the free exchange of goods and services:

Agricultural activity and contempt for order, morals and religion flowed, it would seem, from the same tap, that is, from the rum used as a makeshift currency—a strange instrument of progress but one congenial to that strange company.

Furthermore, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the British Empire adopted a heavily mercantilist approach, structuring trade with its colonial outposts to benefit the mother country. For instance, it focused on successfully breeding the merino sheep in Australia, as raw merino wool was required as an input into the empire’s growing textiles industry, which became highly mechanised during the Industrial Revolution. And by 1850, Australia surpassed Germany to become Britain’s largest wool exporter. Today, Australia contributes approximately half of the world's high-quality merino wool exports.

Ed then goes on to make a series of arguments about how cost-of-living pressures and wage increases are mutually reinforcing, since wages are indexced to the CPI. He then noted the following and cites a passage by Lyndhurst Giblin, the Government Statistician of Tasmania from 1919 and 1928.

So would come to pass the strange vision that fell upon the Tasmanian seer, “of Australia as one enormous sheep bestriding a bottomless pit with statesman, lawyer, miner, landlord, farmer and factory hand all hanging on desperately to the locks of its abundant fleece”.

Ed seems to be a fan of Giblin, calling him a prophet (“seer”) of Australia’s economic future. In his metaphor, Giblin portrays Australia a giant sheep 🐑 with various stakeholders (statesman, lawyer, miner, landlord, farmer, etc) clinging onto the sheep’s fleece. This vision highlights the idea that the entire country and its most important people are dependent on the fortunes of the wool industry. Although Australia has since diversified its economy, it appears that it is now extremely reliant on its resources and mining sector. The sheep has been replaced by iron ore and coal. It comes as no surprise that pastoralism, mining and resources were industries that were heavily supported by British capital. Even today, these sectors remain areas in which Australia possesses a competitive and comparative advantage.

[NB: I wanted to write a bit about the Harvester Case and how it provides historical context to the popular phrase, “a fair days work for a fair day’s pay” but am running out of real estate. It was revolutionary because the case decided how an unskilled labourer could support a wife and three children (and the judge arbitrating the case interviewed the wives of the workers as evidence). the Harvester Case became the “basis of the national minimum wage system in Australia” until the 1970s(?) or so.]

Cocaine dreams

Australia has been fortunate in many ways, and despite its challenges, it remains a blessed country. Which is why it’s a bit funny when a play at the Sydney Opera House satirises cost-of-living pressures faced by Australians. But upon closer contemplation, it seems quite fitting that a prosperous nation would use satire to explore the concept of financial hardship, almost as a way “larp” being “povo” (impoverished). A country truly mired in poverty would not do that. Could it be that Australia is a nation that doesn't fully appreciate the extent of its own good fortune?

The play, written by Italian husband-wife duo Dario Fo and Franca Rame, is set in 1970s Italy, where grocery prices had suddenly doubled overnight. The story revolves around how Antonia had to resort to looting the supermarket to make ends meet, and how she had to enlist the help of her best friend, Margherita, to hide the loot from her husband (he is a staunch Catholic) and the police. Their husbands are struggling to earn enough to pay the bills, and Antonia had to serve him dog food. The play follows Antonia and Margherita’s attempts to outwit the police, resulting in a good mix of slapstick humour and over-the-top fun.

Although the play is based on 1970s Italy, it “feels very 2024” according to the Guardian. For context, Wikipedia describes the economy of 1970s Italy as follows:

The 1970s were a period of economic, political turmoil and social unrest in Italy, known as Years of lead. Unemployment rose sharply, especially among the young, and by 1977 there were one million unemployed people under age 24. Inflation continued, aggravated by the increases in the price of oil in 1973 and 1979.

The “Years of lead” refer to the period where Italy experienced a series of bombings and terrorist attacks perpetrated by both far-left and far-right groups. I don’t know whether drawing parallels between 2024 Australia and 1970s Italy is insulting to Italians.

However, the writer adapting the play for the Sydney Opera House has cleverly added a postmodern twist to the production. During the intermission, a socialist policeman turned to the audience: “I’m looking for a sharehouse” he said (I thought the reference to sharehousing felt very Australian, considering I attended the play with my own housemate). “So if anyone has a spare investment property, let me know”. This line made me think of my neighbours, who indeed own an investment property on the Central Coast, as they are rarely at home in Sydney's inner west.

If anything, the most relevant part of the play was about housing woes in Sydney, how unaffordable it was. I also thought it was funny that the audience was mostly white genx or boomer retirees, and how dissonant it must be for them, as a whole.

The tweeter called it the greatest news headline ever, but to me, it felt like the truest. It reminded me of the Will Anderson comedy show, where he shared a joke about his friend who worked in an office. Upon hearing about cocaine washing up on Bondi Beach, he and his friend decided to take the day off to search for cocaine at the beach.

“We're going to open a cocaine store at the beach,” he declared. He planned to use seashells to scoop up the cocaine and serve it to his patrons (Apparently, cocaine is a very Sydney thing, which I had no idea about). Will suggested the perfect name for the hypothetical cocaine store at Bondi: “He Sells Seashells by the Seashore.” And there was something so indescribably Australian about that story — how it reflects a very seriously unserious culture. Everyone seems to lack the motivation and chutzpah to tackle the housing crisis. Instead, we would rather embark on a whimsical egg hunt for cocaine washed up on our shores.

A measured response: https://tempo.substack.com/p/cringe-or-based-australian-culture

Also reading this: https://www.amazon.com.au/Larrikins-History-Bellanta/dp/1459691938

Australian culture has been about larping as poor, outlawed bushmen ever since we became rich, highly-social urbanites.